Ketris: A Terminal-Based Tetris Clone in Kotlin

Sometimes it’s fun to try a new challenge, and sometimes it is fun to mix a few challenges together. That is how I decided to make a Tetris clone for the terminal using Kotlin… on the JVM.

Background #

A couple of years ago, I ran across Lanterna, which is a Curses-style library, built to run portably on the JVM. I thought this was an interesting library, if a little hard to justify in normal use-cases. Generally speaking, if you’re going to build a terminal interface, using Java isn’t the first choice if only because of startup performance and initial resident memory use. That said, for long-standing applications running in a headless environment, there seemed to be a potential, however small, for this to be a useful library with which to have some experience.

Sometimes I also like to tinker with game programming. In a previous life I spent a good bit of time in the gaming industry, and while I mostly focused on server infrastructure, there was a ton of unique and fun challenges in that space that I occasionally miss.

Given these two motivations and the fact I’ve always liked Tetris, I got the crazy idea to try to build Tetris, for the command line, using Lanterna. Hence, Ketris was born.

High-Level Structure #

The current project is actually quite simple. It follows a fairly standard “game loop” iteration:

- Process Input

- Update Game State

- Update Display

- Handle Game Tick/Time Management

Today, this is simply baked into a very basic loop managed by the clock code:

val clock = Clock()

val game = Game(clock)

val input = Input(screen, game)

val graphics = Graphics(screen, game)

var inputState = InputState.EMPTY

clock.loopUntil({ inputState.eof }) {

inputState = input.process()

game.handle(inputState)

graphics.repaint()

}

As this illustrates, the various bits of the game “layers” are split into separate concepts in the app model. In fact, there are only a few files overall each with pretty clear responsibilities:

Ketris- This is home to the main function, which establishes global state for the game, such as the screen, input, game, and graphics, and also bootstraps the core game loop.Clock- The clock helps with managing the game tick based on common tetris game rules, and feedback from the game logicShapes- The shapes enumeration defines the common “tetrominoes” for Tetris, including their default coordinates and shapeInput- The input class translates command-line input into a logical input state that can be processed per-loopGraphics- This class understands how to map the current game state into Lanterna rendering commandsGame- The high-level Tetris game logic exists in this class, including calculation of scores and game speed (gravity) based on lines collapsedBoard- The board is managed by theGame, and contains current piece and “cell” state for the game, and calculates matches and line scores

Drawing with Lanterna #

Lanterna is an interesting library, and makes building terminal-based UIs quite straightforward. One of the major benefits of Lanterna is that it can also emulate a terminal using a Swing-based window on any system with a graphical UI. It can make choices of which to use based on your preference:

- If a graphics runtime exists, favor the emulation window

- If a TTY exists (or whatever the Windows headache situation is), favor the terminal

- Force one way or another

For Ketris I’ve currently chosen to favor the native terminal if it is available, using this code:

DefaultTerminalFactory()

.setPreferTerminalEmulator(false)

.createTerminal()

Once a Lanterna Terminal is created, the UI for the application is built against a Screen, which is an abstraction of the viewport for the app. There is a TerminalScreen (direct to the terminal) and a VirtualScreenn which can enable/enforce a minimum viewport size with scrollbars.

Rendering to the screen can be done directly against the screen, but most times it makes sense to use the TextGraphics API available via screen.newTextGraphics(). This object has a variety of handy abstractions for drawing various shapes to the text UI, including:

- Statefully retains the current foreground and background colors for subsequent rendering operations

- Draw and fill lines, rectangles, triangles, and “text images” (which are basically pre-baked sprites of characters)

- Draw strings of text, including using Control Sequence Introducers (CSIs) and Select Graphic Rendition (SGR) modifiers

- Tab rendering behavior management

This API makes rendering most things quite straightforward - for example, here is some code that renders that “current game stats”:

foregroundColor = STATS_COLOR

putString(INFO_START, 3, "Level: ${game.level}")

putString(INFO_START, 4, "Lines: ${game.lines}")

putString(INFO_START, 5, "Score: ${game.score}")

if (!game.isRunning()) {

foregroundColor = PRESS_SPACE_COLOR

putString(INFO_START, 6, "Space to Play")

}

Under the covers, the Screen uses a “back-buffer + front-buffer” concept, and when drawing to the screen, all changes are made to the back-buffer. To get the screen to update, after rendering the screen must explicitly be told to refresh(). This will apply the changes from back-buffer to front-buffer. Lanterna attempts to do calculations on the amount of actual changes between the two matrices of characters on whether it should do a “delta” rendering update or a “full redraw” of the screen; and it does this based on some internal calculations looking for 75% of the UI being changed.

Lanterna Inputs #

The other part of the Lanterna API that can help with building text UIs is input processing, which is fundamentally important for a game like Ketris. To enable this, Lanterna has the concept of an input queue on the screen, and application code can simply opportunistically poll for input, which is perfect for a game loop where the app wants to peek for input opportunistically but not wait. Out of this the application can get a variety of potential values encoded as either a KeyStroke or null.

Within Ketris this is simply mapped into an InputState object that contains the behavior to take based on the last input:

val key = screen.pollInput()

return when {

key == null -> InputState.EMPTY

key.keyType == KeyType.Escape || (key.character == ' ' && !game.isRunning()) -> InputState(togglePause = true)

key.keyType == KeyType.ArrowUp -> InputState(rotate = Rotation.Clockwise)

key.keyType == KeyType.ArrowDown -> InputState(rotate = Rotation.Counterclockwise)

key.character == ' ' -> InputState(drop = true)

key.keyType == KeyType.ArrowLeft -> InputState(xDelta = -1)

key.keyType == KeyType.ArrowRight -> InputState(xDelta = 1)

key.keyType == KeyType.EOF -> InputState(eof = true)

else -> InputState.EMPTY

}

This basically includes the mechanics for:

- (Un)pausing the game

- Rotating the piece

- Speed-dropping the piece

- Moving the piece left or right

- Detecting the termination of the screen

KeyType.EOF is detected when the screen is destroyed, which can happen programmatically (via close()) or via external inputs.

On Clocks and Gravity #

To enable variable game speed but constant input processing and game state processing speed, the clock has a fixed tick rate of ~60 updates per second. From that, the various speeds of the gameplay can be extrapolated. This means that generally the clock simply looks like this basic loop (Note: there are more advanced ways to manage clocks to avoid drift and time under-runs and such, but for a game like this, a simple delta-based clock seemed plenty adequate):

while (!predicate()) {

val loopStart = System.nanoTime()

action()

val duration = LOOP_TIME.minus(Duration.ofNanos(System.nanoTime() - loopStart)).toMillis()

if (duration > 0) Thread.sleep(duration)

}

To simulate pieces moving in the game board, there is a concept of “gravity”, where-by a piece has a certain fall rate based on the state of the game (i.e.: level, notably). Gravity in Ketris is modeled as a positive integer, with 1 being the lowest amount of gravity, and 15 being the highest. The fall-rate for a single piece is computed as a percentage of row fallen per-frame, 60 times per second. Every time a frame is advanced, the number of frames a piece has been active is compared against a calculation of how many rows the piece should have dropped in that number of frames, which is based on the velocity table. For each frame, a piece may fall 0 to N places.

Movement and Collisions #

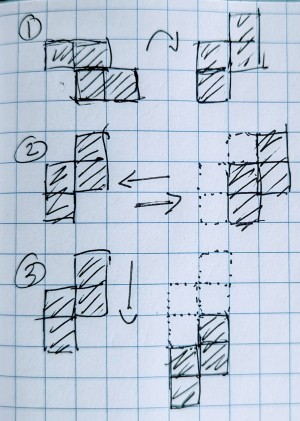

One other detail I thought was kind of interesting was the mechanics of piece collisions. To do all of this, there is a data structure called Board, which contains the active piece, the “hold” piece that renders as the next piece to come, and the matrix of cells representing each “block” on the board, with each cell being aware of anything that might overlay it.

The actual movement algorithm is roughly this:

- Calculate any movement by gravity

- Apply any rotations, looking for collisions and canceling if it would cause one

- Apply any horizontal movement, looking for collisions and canceling if it would cause one

- Apply any gravity movement, iteratively by row, looking for collisions

- Once a collision is found, “place” the piece, and clear any lines that are fully blocked out

- Shift any floating cells down

There are a variety of ways and algorithms to detect collisions, which as illustrated above shows up in at least three separate parts. I chose the most naive and simple algorithm, as refined performance was not a fundamental concern given the relative tiny size of the game board. The actual collision rules are simple: will the new shape as placed in the coordinate space collide with either (a) the game board edges or (b) any of the cells in the game board that contain a previously placed piece. However, this algorithm, as written, is actually quite inefficient (as typical game programming would go) for a number of reasons:

- Multiple transformations are individually applied to the shape, and each one is a full immutable copy of the prior shape

- Each transformation may result in a collision, in which case the transformed copy is thrown away

- The internal data in the piece data structure is wasteful, especially the use of nullable “big-i” integers for the live shape

- All cells are checked, when in reality we can know ahead of time which cells can never be checked and build a more intelligent search algorithm for potentially collide-able cells based on the max-y of the piece.

Ideally more in-place, primitive-only, smart-data-structure operations should be used in this algorithm to avoid the potential per-frame memory and latency overhead of this algorithm. However, there is one big benefit to this algorithm as-written: It is tremendously simple to read and reason about, as the copy can just be thrown away, leaving the original in place.

For example, here is how the code keeps track of conditional translation and rotation of the piece:

val priorPiece = activePiece

activePiece = activePiece.rotate(input.rotate).takeUnless { collides(it) } ?: activePiece

activePiece = activePiece.move(input.xDelta, 0).takeUnless { collides(it) } ?: activePiece

Ghost Piece #

The ghost piece (current target location) is another interesting detail, but really just a variant of the regular movement code. Each time the active piece rotates or translates, the ghost is recalculated, simply moving the height down until it collides with a cell.

Rendering of Cells #

To help with rendering, each cell keeps track of three separate things:

- An active piece overlay

- A ghost piece overlay

- A previously placed piece template

Across all three, the only thing a single cell really cares about is the color (that’s all we render), but really it keeps a reference to the shape template from which the piece came (which today indirectly leads to the color). As a result, when choosing to draw a character or a blank, the process is simply this:

val shape = cell.shape() // any of the above three

val (color: TextColor, char: Char) = when {

shape != null && it.isGhosted() -> GHOST_COLOR to GHOST_CHAR

shape != null -> PIECE_COLORS[shape]!! to PIECE_CHAR

else -> BLANK_CELL_COLOR to BLANK_CELL_CHAR

}

foregroundColor = color

setCharacter(x, y, char)

As a result, to satisfy the graphics, when moving pieces on the game board, the state of these three things simply needs to be adjusted on the cell each frame based on the mechanics of the game.

Other Ideas and Next Steps #

As it is now, it’s a pretty basic implementation of the game mechanics and rendering. Here are some thoughts that occurred to me as directions to take this little toy project:

- Scaling UI - as is, the 1x scale can be pretty minuscule depending on the chosen terminal font

- Different Game Modes - the current game mode is a very basic linear progression with basic gravity mechanics - there are many variants and fun additions worth exploring

- Fanfare - The UI currently has no animations to indicate lines, getting a tetris, leveling up, or crashing and burning. It’d be interesting to explore things like flashing and block sweeps to make it feel more alive

- High Score Board - Scores are thrown away after retry today

- JLink / Native Compilation - It’d be a fun project to try to natively package this given that it’s a relatively simple reflection free project. It would help with startup performance, if nothing else

- Kotlin Multiplatform - Another alternative (that would require abstracting Lanterna) would be to explore a JVM or Kotlin-Native (or other targets like JS and WASM) as a way to explore the edges of building multiplatform Kotlin objects with platform-specific components

- Compose Multiplatform UI - Building the game UI using the SKIA-based compose multiplatform would enable targeted desktop, browsers, and phones

- LibGDX UI - Another option would be to port this game to LibGDX, though admittedly that is a more of a rewrite than a port, as LibGDX has a fundamentally different “game loop” and a very specific concept for everything from UI, input, and game logic management

- Sound - It’d be fun to try to look for options in terms of sound devices available to play some degree of sounds (depending on capabilities) on various events

- Configurable colors/themes - Today all the ansi coloring choices are just constants, but they could be customizable

- Localization - While there isn’t much text, it’s all US English only today

You may look at this list and think “why? - there are a ton of other perfectly good Tetris clones built in platforms more appropriately suited for what they are doing”. And honestly, you’d be right - frankly, the only reason is the same as any reason to take on any personal project like this - to learn and explore the edges of various technology and approaches. If it motivates you, it’s worth it!