Distilling JRuby: Method Dispatching 101

To better understand how JRuby combines the Java world with the Ruby world, I have recently been delving into the source code (available via git), and while the implementation there-in is always bound to evolve and change, it seemed that there would probably be some value in me documenting my journey through the guts of JRuby.

JRuby is a huge beast, so it can be hard to find a place to start - nonetheless, as the joke goes you eat an elephant one bite at a time, so I figured I’d start somewhere at least somewhat familiar.

One of the first areas I picked up was the method dispatch code. This is an area I have seen discussed through a number of blog entries by various JRuby committers; and given the criticality of the code in this area, I knew it was probably a fairly mainstream section of functionality; heavily used by a running JRuby application.

Unfortunately, it is also right in the middle of the implementation, so it’s a bit like starting to eat the elephant right in the middle. Nonetheless, I have made my way through a good bit of it, and learned a lot in the process, so let’s get started.

Article Series

- Distilling JRuby: Method Dispatching 101

- Distilling JRuby: Tracking Scope

- Distilling JRuby: The JIT Compiler

- Distilling JRuby: Frames and Backtraces

Disclaimer: I am admittedly an amateur when it comes to the JRuby code. Nothing I say on here should be considered JRuby gospel; consider it a diary of my understanding of the code, and a good starting point for your analysis should you want to make one. I welcome any constructive input on where I may have gone off the reservation.

First, the concept: Any Ruby implementation has to take the code written by a developer, parse it, and then translate it into a series of execution steps. Effectively every method written in Ruby is going to call other methods (even the venerable puts 'Hello World' requires the ‘puts’ method). Therefore, it’s critically important for a Ruby implementation to be able to dispatch invocations of methods by a developer to the appropriate method implementations. So, the real question at the center of all of this is after JRuby parses your code and sees that you want to call the method ‘puts’, how does it know:

- Where to find ‘puts’?

- How to call ‘puts’?

- How to give you the result from ‘puts’?

Method Handles #

One of the primary classes in the middle of all of this framework is org.jruby.internal.runtime.methods.DynamicMethod. I’ll quote the Javadoc (as of JRuby 1.3.x):

DynamicMethod represents a method handle in JRuby, to provide both entry points into AST and bytecode interpreters, but also to provide handles to JIT-compiled and hand-implemented Java methods. All methods invokable from Ruby code are referenced by method handles, either directly or through delegation or callback mechanisms.

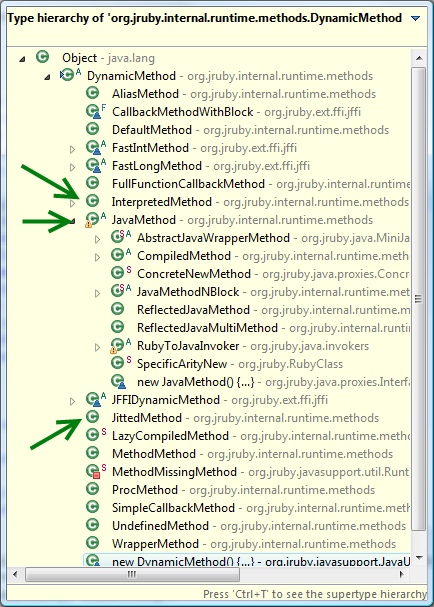

The DynamicMethod class, as the documentation suggests, is the primary handle JRuby uses to reference another block of code. It turns out that DynamicMethod is the abstract parent class of several method implementations:

What we can determine from this is that as JRuby is interpreting your code it is collecting, and in turn invoking, DynamicMethod objects representing the various calls being made. Distilling the various implementations, we can see that each one is tailored to a specific type of call:

InterpretedMethod - Has a handle on an AST node representing the code of that method. Eventually asks the AST node to interpret itself.

JittedMethod - Counterpart to the interpreted method. JRuby has an innovative JIT compiler that translates Ruby code into a series of Java bytecode instructions. This bytecode is then stored and executed via a loaded Java class. Several blog entries could be spent explaining the internals of this one.

DefaultMethod - Special “shell-game” method that can either interpret or use a JIT’d method as returned by the JITCompiler. Internally manages the handle to one of the two methods for clients, telling them which reference to cache. Since the JIT operates on a threshold, this method may interpret on the first several calls before swapping out to a JIT’d variety.

JavaMethod- Top-level class for any method handle that makes a call into Java. The majority of the core Ruby libraries are implemented in Java in JRuby (just as they are largely implemented in C for Ruby). There are a number of specialized Java method handles. The most straightforward general-purpose implementation is ReflectedJavaMethod, which simply makes a reflected call into the Java counterpart, however it’s not going to be the most commonly used now-a-days, as we’ll see.

At a high-level, these method handles provide a fairly good abstraction of how one block of code talks to another. But how does it know which type of method handle to use when? They have to come from somewhere. It’s simplest to think of the steps taken by JRuby in interpreted mode, as that is how all methods generally start, and certainly how the top level of your script will be invoked.

Chaining Method Invocations #

First - all scripts/methods/etc are translated into an AST of org.jruby.ast.Node objects. All Node objects have an ‘interpret’ method call, the concept being that as the AST is being traversed, the various nodes provide the actual interpret algorithm (a fairly standard approach to implementing an interpreted language). Without spending a lot of time delving into the actual node implementations, you can see kind of how this works by looking at a relatively simple node: the AndNode (representing &&). As of 1.3.X, here is the interpret method of AndNode:

@Override

public IRubyObject interpret(Ruby runtime, ThreadContext context, IRubyObject self, Block aBlock) {

IRubyObject result = firstNode.interpret(runtime, context, self, aBlock);

if (!result.isTrue()) return result;

return secondNode.interpret(runtime, context, self, aBlock);

}

As you can see, it simply interprets the two sibling nodes looking for true - you can also see how they implement the expected short-circuit behaivor on the first node.

Anyway, back to method calling. In this hierarchy of nodes, method calls are generally represented by some variant of the org.jruby.ast.*CallNode object (there are a variety of implementations and subclasses depending on the type of receiver and number of arguments). CallNode objects internally use an instance of org.jruby.runtime.CallSite to invoke all methods. These CallSite objects provide an abstraction of the point of invocation of a method. They perform caching to improve performance for the interpreter, and represent different types of calls depending on the case (there are CallSite hot-wirings to handle >, <, =, and so forth when running in -fast mode for example).

For the most part, however, the method lookup proceeds from the CallSite through what is called the ‘receiver Node’, or the AST node representing the receiver of the method call. As it is running, the parser constructs a node for all variable references in the code (LocalVarNode, InstVarNode, DVarNode, GlobalVarNode, etc). These variable references know how to look themselves up in the current scope. JRuby tracks the current call stack via the object org.jruby.runtime.DynamicScope, which, while being a critical component of this process, for this discussion I will simply hand-wave as something that tracks the currently available variables; how it does so can be analyzed deeper in the future. (Additionally it should be noted, the parser, which is invoked at runtime, uses the current static scope to determine what type of variable node should be created).

As an example, here is the interpret implementation of LocalVarNode which represents a local variable:

@Override

public IRubyObject interpret(Ruby runtime, ThreadContext context, IRubyObject self, Block aBlock) {

IRubyObject result = context.getCurrentScope().getValue(getIndex(), getDepth());

return result == null ? runtime.getNil() : result;

}

As you can see it simply asks the current scope (the DynamicScope object at the moment) to find the object given the index and depth of the variable node. Assuming there is no error in the Java code, the lookup on the scope for the variable node will come back with an IRubyObject representing the variable. This can then be used to find the appropriate RubyClass, which can then in turn be used to find a method that matches the signature being called.

This is an important point - we are looking up the corresponding method at runtime by analyzing the object held in the variable - there is no compile-time binding to the method. The magical JIT-ing done by the JRuby committers will bring this a lot closer to a compile-time binding (as will invokedynamic), however all of those features really just hot-wire a runtime-discovered binding. In short, Ruby (without any fancy type-assistance like that implemented Duby or Surinx) will always runtime-bind variable types, which is both good (for capabilities) and bad (for relative performance limitations).

Anywho – way down in the bowels of CallSite, there is a call against the RubyClass for the object that is against the method RubyModule#searchMethodInner. This method looks like this:

protected DynamicMethod searchMethodInner(String name) {

DynamicMethod method = getMethods().get(name);

if (method != null) return method;

return superClass == null ? null : superClass.searchMethodInner(name);

}

As you can see, this is a basic recursive algorithm that looks in what is effectively a hash-map of methods for a DynamicMethod handle. So we’ve now made it all the way to our method handle.

Loading Classes and Methods #

Even though we have traced the invocation process to where the method handles are sourced (the owning class), what we haven’t seen yet, is how the methods are actually loaded into the RubyClass. Where did that magic hashmap of methods come from? As with everything in JRuby - it depends.

Loading Ruby Classes #

If the class being loaded is implemented in Ruby, the load process is much like the method dispatch process. The various AST nodes work together to load the class into the runtime. Ignoring the majority of the class-load semantics (they are interesting, but not particularly relevant here), we can jump straight to the abstract MethodDefNode, which has two child methods: DefnNode and DefsNode - Defn represents standard method definitions, and Defs represents singleton methods.

The standard methods eventually boil down to this sequence of events:

DynamicMethod newMethod = DynamicMethodFactory.newInterpretedMethod(

runtime, containingClass, name, scope, body, argsNode,

visibility, getPosition());

containingClass.addMethod(name, newMethod);

In other words, JRuby is creating a new ‘interpreted’ method (which, as discussed previously, will normally be a DefaultMethod object), that has the body, args, and other meta-information available to it for if/when it is invoked.

The code then adds the method to the RubyClass magic-map so that later it will be returned when the CallSite asks for it via ‘getMethods()’.

All things considered, fairly simple.

Loading Java-Backed Classes #

The story behind Java-based classes is a little more tricky - for one thing, it depends on if we’re dealing with a core library, or a user-provided Java object wrapped by the Java integration support.

As I mentioned previously, several of the core libraries in JRuby are implemented in Java. This is done both for performance reasons, and for the simple fact that some of the core libraries (Kernel for example) cannot be implemented in Ruby as they are needed for all other Ruby objects to function.

In any case, during JRuby startup, the method Ruby#initCore() is called. This in turn, loads a number of Java peers. Some examples include:

org.jruby.RubyKernelorg.jruby.RubyIOorg.jruby.RubyStringorg.jruby.RubyInteger

… and the list goes on. All of these have an associated RubyClass object that needs to have Java method handles in its ‘methods’ collection. What #initCore does is pre-fill these various method handles by calling special static methods on these core classes. The majority of these static initializers on the core classes wind back up to a method on RubyClass called defineAnnotatedMethods. This method uses an API called TypePopulator, which exists solely to bind Java methods to Ruby classes.

But how does it do it?

In all cases, these special Ruby-library-implementing Java classes must use a special suite of Java annotations to mark what methods on their corresponding Ruby class they are providing. Here is RubyKernel.puts for a concrete example:

@JRubyMethod(name = "puts", rest = true, module = true, visibility = PRIVATE)

public static IRubyObject puts(ThreadContext context, IRubyObject recv, IRubyObject[] args) {

IRubyObject defout = context.getRuntime().getGlobalVariables().get("$>");

return RubyIO.puts(context, defout, args);

}

These annotations come in a variety of flavors depending on the case. For example, if we were to look at RubyString.chop, you’ll see there are actually two implementations: one to support Ruby 1.8 and one to support Ruby 1.9 (as it was bug-fixed/altered in 1.9 to support string encodings):

@JRubyMethod(name = "chop", compat = CompatVersion.RUBY1_8)

public IRubyObject chop(ThreadContext context) {

if (value.realSize == 0) return newEmptyString(context.getRuntime(), getMetaClass()).infectBy(this);

return makeShared(context.getRuntime(), 0, choppedLength());

}

@JRubyMethod(name = "chop", compat = CompatVersion.RUBY1_9)

public IRubyObject chop19(ThreadContext context) {

Ruby runtime = context.getRuntime();

if (value.realSize == 0) return newEmptyString(runtime, getMetaClass(), value.encoding).infectBy(this);

return makeShared19(runtime, 0, choppedLength19(runtime));

}

As you can see, these annotations have a compatibility flag to determine which version of Ruby the implementation supports.

The TypePopulator class is meant to scan the corresponding class for these annotations, and turn them into DynamicMethod objects that can be registered on the RubyClass. There is a default (naive) implementation of TypePopulator that does this at runtime in a fairly straightforward process. However, there is also an APT build process to generate special instances of TypePopulator at compile-time that are then stored in the org.jruby.gen package. These TypePopulator implementations exist on a per-class basis, and have the Java method registrations ‘hard-coded’ in them as individual lines. This is meant to significantly improve the initial load time for the Java libraries.

The defineAnnotatedMethods method previously mentioned boils down to trying to lookup these TypePopulator objects at runtime, falling back to the default if it can’t find them:

try {

String qualifiedName = "org.jruby.gen." + clazz.getCanonicalName().replace('.', '$');

if (DEBUG) System.out.println("looking for " + qualifiedName + "$Populator");

Class populatorClass = Class.forName(qualifiedName + "$Populator");

populator = (TypePopulator)populatorClass.newInstance();

} catch (Throwable t) {

if (DEBUG) System.out.println("Could not find it, using default populator");

populator = TypePopulator.DEFAULT;

}

The methods actually registered in the method collection are very different than those we registered before. Since they are fronting Java methods, they can’t be simple recursive ‘interpreted’ methods. Instead, they have to use a different mechanism. The original tie was the ReflectedJavaMethod, which would simply use reflection to call the Java peer. Some time later (1.1 JRuby I think?), Charles Nutter implemented a special Java method that compiles a ‘mini-class’ that invokes the method via compiled bytecode, which is much faster (and easier for Java to JIT) than the reflection code. This is captured as a generated subclass of CompiledMethod.

As for Java objects that are provided by the user, and are in turn handled by the Java integration support, I hate to delve too deeply in this for a few reasons:

- Java classes, unlike Ruby, have a ton of special cases that make the code very tedious to parse.

- The JRuby crew is working on revitalizing this code in earnest as part of the next release of JRuby, so whatever I cover here will be out-of-date very soon.

However, in concept it’s fairly simple. A RubyClass is constructed and cached for the Java class (by iterating it’s class metadata). In that Ruby class, a special method peer (of one of the above types) is constructed that binds to each corresponding Java method. Note that the Java integration jumps through some hoops to provide Ruby-syntax-ish method names, which were all covered in the EngineYard blog entries.

Once that class is created and bound to the runtime, it can function like any other RubyClass.

Incidentally, that is how adding a method to a Java object is made possible; it is simply bound to the RubyClass peer (that’s also why the Java peer can’t see it).

In Closing #

This was not so brief, but was about as short as I could make it and still cover all high-level components of the method dispatching in JRuby.

There is a lot more Ruby internals to touch on in the future, so stay tuned!