JVMLS 2017: Pattern Matching in Java

This year at JVMLS, Brian Goetz talked about Pattern Matching on the JVM and how it might be modeled. In particular he spoke about:

- How Scala does it

- How C# does it

- How Java might do it

- How Java could do it with amortized constant-time Matching

He breaks pattern matching down as a two-step process for most languages:

- Test/Match - This is where a (perhaps quite complex) conditional is matched at runtime against an actual object (even comparing nested matchable types)

- Destructuring - This is the process of taking key important parts (often denoted by the match) out of the corresponding object and establishing those values as variables in the local namespace of the case being evaluated.

The simple example provided is one of dealing with a variable-typed input routed to several output behaviors - in this example to detail with all “primitive-like” types and then all other types:

Object someVal = // input from somewhere

String result = switch(someVal) {

case Integer i -> String.format("int %d", i);

case Byte b -> String.format("byte %d", b);

case Long l -> String.format("long %d", l);

case Double d -> String.format("double %f", d);

case String s -> String.format("string %s", s);

default -> "unknown type";

}

This is not valid Java, but rather shows what pattern matching might look like in Java. In this simple example, the case clause is both matching as a type (e.g. Integer) and destructuring to a variable (e.g. i). In the enclosing context, it is known that that i is an Integer and can be used as such.

This isn’t any different than instanceof and casts except it is more concise without really losing any clarity. It also avoid repeating logic (casts in Java are almost always preceded by a matching instanceof, as a concrete example).

Additionally with this example we can see that this imaginary switch statement is an expression, meaning it can return a value, and the compiler will ensure that the value returned from all branches is type-safe (in this case can be bound to String result).

A more sophisticated example dives into AST analysis of a calculator style input (which is a typical example in pattern matching). In this case there is an int node (single param), a negation node (single param), an addition node (two params), and a multiplication node (two params). The goal is to use pattern matching to compute the result of a node tree of these types. For example:

5 + 10 * -13

This could be parsed into this node tree:

AddNode(

IntNode(5),

MultNode(

IntNode(10),

NegNode(

IntNode(13)

)

)

)

To compute this with pattern matching, you could model this in this way:

int eval(Node n) {

return switch(n) {

case IntNode(var i) -> i;

case NegNode(var n) -> eval(-n);

case AddNode(var l, var r) -> eval(l) + eval(r);

case MulNode(var l, var r) -> eval(l) * eval(r);

}

}

You can probably see that, given this pattern matching switch, if you have an int node, you get the destructured integer value of the node, where-as any other node type is simply destructured into its underlying Node type and evaluated recursively.

Where Brian’s talk gets particularly interesting is how the JVM might model the implementation of destructuring for a data type. The process of destructuring is one where you take a type and boil it out into the composing parts. He talks about Scala first, which uses the unapply method to destructure into an Option[Tuple[...]] of the various parts:

def unapply(p : Point) : Option[Tuple[int,int]] = Some(p.x, p.y)

The major downside here is the overhead required to do this. Every destructure requires the construction of a whole stack of heap-allocated objects to wrap the underlying set of elements.

C# also has a similar concept, but has language support to make it cheaper:

public static void Deconstruct<T1,T2>(this Tuple<T1,T2> tuple, out T1 item1, out T2 item2)

Here, you are using “out” parameters in the method, which are basically “multi-return types” for any particular method in C# (avoids creating the output Option/Tuple types like Scala has to do).

For those curious, Kotlin already supports destructuring at the language level via the convention of implementing componentN() functions. See Kotling Destructuring for more details.

One of the interesting elements he points out is that often times when you wind up with a complex “match” type, you have done some amount of non-trivial computation to get to the point you realize it matches. To then get to the destructuring of that complex type, you need some way to carry data from step 1 to step 2, or you have to repeat all of the digging in step 1 and step 2 (which is all too common in pattern matching implementations).

The idea he proposes is to support a method-handle based implementation that results in calls in these forms:

public interface DtorHandle<T> { // destructor handle

MethodType descriptor();

Class<?> carrierType; // the type that carries from step 1 and 2

MethodHandle precompute(); // get a method that returns a carrier type for 1 and 2. Step "0"

MethodHandle matches(); // get a method that matches using the current value and the carrier type

MethodHandle component(int n); // get the component at position N of the match using the existing carrier type

}

Here is some pseudo-code that might use this destructor-based mechanism:

Object objToMatch = // ...

DtorHandle dc = // ...

C carrier = dc.preprocess().invoke(objToMatch);

if(dc.matches().invoke(objToMatch, c)) {

// generated by runtime compiler assuming this type has two components (int,int)

int x = dc.component(0).invoke(objToMatch, c);

int y = dc.component(1).invoke(objToMatch, c);

// ...

}

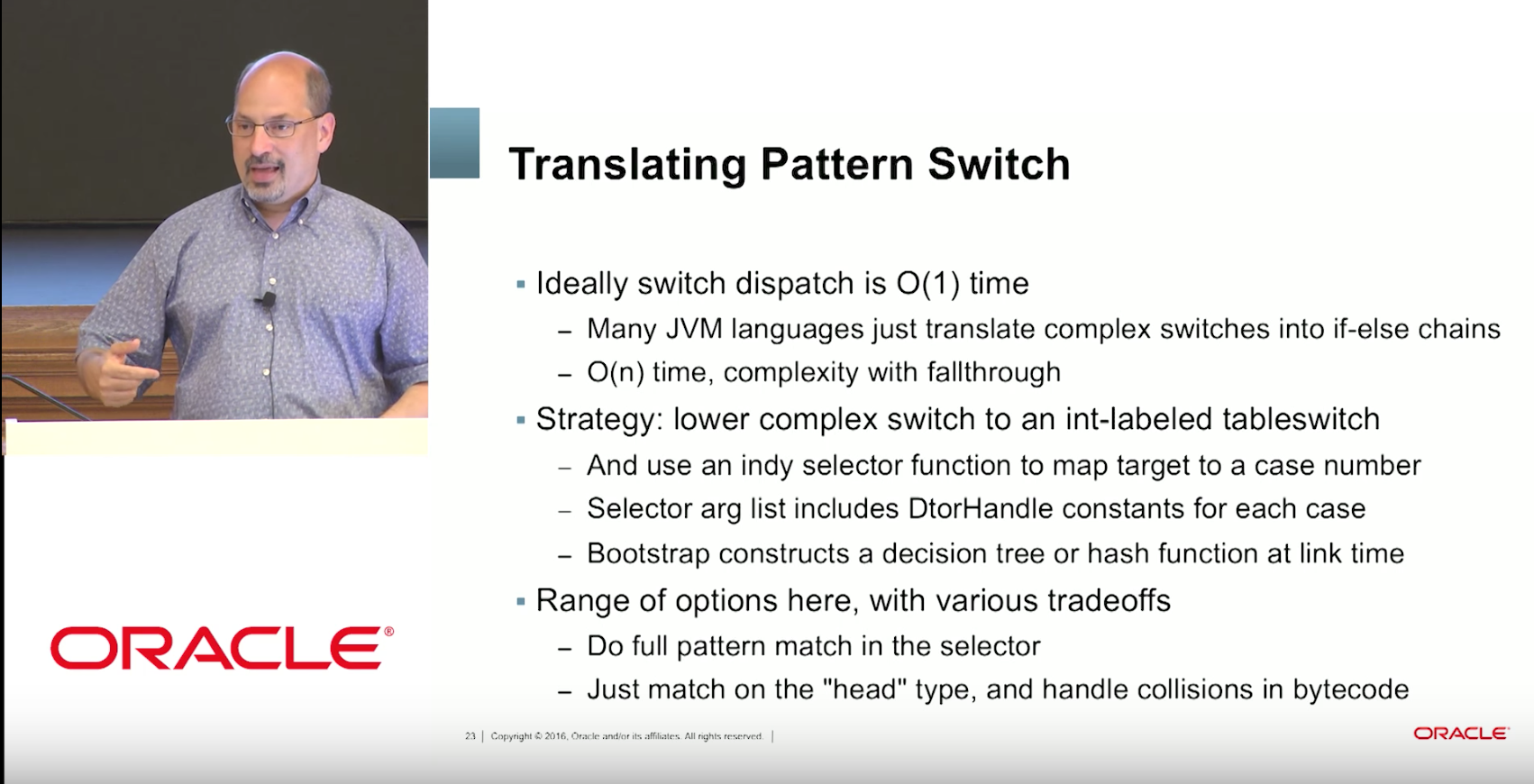

As Mr. Goetz points out, this inlines beautifully, can further rely on LDC to make it more efficient, and with some clever trickery, can even be made to use table switching for amortized constant-time pattern matching for many cases:

By using a pattern like (but perhaps not exactly matching) this interface, such that the expected call-sites are factories (similar to the lambda meta-factory approach), the hotspot compiler (or any JVM runtime) has a lot of tools available to optimize as it sees fit. It may be able to detect ahead of time that much of the work isn’t required in most cases.

You can watch the enlightening talk here: