Distilling JRuby: Tracking Scope

One of the things that is always going on in any programming language is managing the scope of variables. Scope is central to both how we code, as well as how a program executes. Even just in methods, how variables are scoped can be a point of great contention (particularly in code reviews).

When it comes to implementing a programming language like JRuby, the concept of a scope permeates everything. After all, someone needs to track what variables are available at each level in the activation stack, and when the stack unwinds (either through normal use, or due to an exception), someone needs to unbind the variables in scope with it.

And, of course, Ruby has closures, which means that you have to carry (aka capture) free variables into scope of the closure.But, Ruby also has instance and class eval’ed code blocks. Those have an entirely different scope. When you get down to it, Ruby is bound to test a scope algorithm’s limits.

So how does JRuby do it?

Article Series

- Distilling JRuby: Method Dispatching 101

- Distilling JRuby: Tracking Scope

- Distilling JRuby: The JIT Compiler

- Distilling JRuby: Frames and Backtraces

In my previous Distilling JRuby article I briefly mentioned a class called ‘DynamicScope’. I also hinted at another object called ‘StaticScope’. Both play a central role in handling this difficult problem.

The Static Scope #

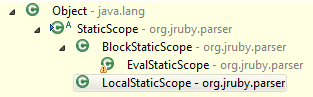

Static scoping in JRuby is all about the variable access as seen by the parser. From a class-hierarchy standpoint, it’s fairly simple, as Figure 1 indicates.

org.jruby.parserWe’ll get into the differences of these types momentarily. As the parser is traversing the language syntax, it creates a stack of static scope objects. The majority of the parser code is generated, so it’s not particularly beneficial for me to provide examples from the code on how it does this, but at a high-level calls are made at certain points in the parse routine to the methods ParserSupport.pushBlockScope, ParserSupport.pushLocalScope, and ParserSupport.popCurrentScope. These, as the method names indicate, create new scope objects as children of the current scope. Once created, they then subsequently become the current scope, and the old current scope is now their ’enclosing’ scope.

When certain nodes of the AST tree are created (block and method nodes most notably), they are handed a StaticScope object representing their scope in the tree (from the parser, via ParserSupport.getCurrentScope()), which they will later use to execute. For example, when a method definition is hit by the parser, it is going to:

- Push a new local static scope on to the stack

- Create a MethodDefnNode object, passing the current static scope in.

- Pop the local static scope from the stack

This method will effectively have a dedicated scope object associated with it; however there is only one StaticScope object for that method definition, no matter how many times it is called, hence the term static. The static variants of the scope are really templates defining what the parser has determined is available in that particular scope.

This method, when it is interpreted (as we saw in the previous article), will then create a new DynamicMethod object, which usually holds on to a copy of the static scope for the method. Later, I will discuss how it will use that static scope when it is invoked.

Blocks, like methods, will go through a similar construction phase, however blocks are given a BlockStaticScope object (as the name suggests). This scope is aware of the special scoping rules that Ruby blocks have.

Handling Variables #

As the parser is working, it will also hit variable assignments and declarations. In these cases, the previously-created scope (whether for a block, or a method) is consulted. This allows the scope to learn about its internal elements (recording variables), and also allows the scope (which can be one of a few types) to help translate the token into an appropriate AST node (different nodes interpret different ways depending on the type of code being run).

Variable declaration is an interesting problem in Ruby implementations. In many languages (particularly compiled, strong-typed languages), when a variable declaration is hit, there is generally some sort of identifier: in Java there is always a type declaration; similarly in Scala, there is the val and var keywords. Admittedly, these languages use those keywords for a purpose (typing and mutability respectively), however it also gives their respective compilers something to hold onto as the first declaration of the variable. Any references to that variable prior to that point are invalid.

Ruby, on the other hand (like many dynamic/scripting languages), doesn’t have this sort of handle; the language itself doesn’t have the concept of declaration. Instead, the first time you assign a variable is, in fact, when you declare it. So, in short, when JRuby finds an assignment, it could also be a declaration. The parser needs the scope to help it make this determination.

On the other hand, even though declaration is implicit in Ruby, the terminology “declare” does show up in the JRuby source - in this case, what is meant by “declare” is really when a variable is referenced (such as when used as the right hand side of an assignment).

Understanding the Parser #

When trying to understand the scope algorithm, a bad handicap is not understanding the node hierarchy created by the parser; after all the node hierarchy in JRuby is what drives the scoping routine (and for that matter, the invocation of the program). So what does the parser actually see when given any particular program? For example, let’s try this very simple Ruby script that juggles some basic variables:

a = 3

b = a

Thankfully, because JRuby is easily accessible from Java, we can write a quick Java program to spit out the node hierarchy as seen by the JRuby parser. Note that (and this may be an obvious comment) this only parses the top-level script; any method calls to other libraries are not traversed.

import java.util.List;

import org.jruby.Ruby;

import org.jruby.ast.Node;

public class NodeEmitter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Node n = Ruby.getGlobalRuntime().parseFromMain(ParserInterpreter.class.getClassLoader().getResourceAsStream("test.rb"), "test.rb");

printNode(n, 0);

}

private static void printNode(Node n, int depth) {

for(int i=0; i<depth; i++) {

System.out.print("\t");

}

System.out.println(n.getNodeType().toString() + " pos: " + n.getPosition());

List<Node> children = n.childNodes();

for(Node child : children) {

printNode(child, depth+1);

}

}

}

(There are much more ‘creative’ ways to instrument the running system to get information as it runs, but for the purposes of this analysis, this gives us a lot of valuable info.)

If we spit out the node hierarchy of our Ruby script using this tool, we’ll get this in the console:

ROOTNODE pos: test.rb:0

BLOCKNODE pos: test.rb:0

NEWLINENODE pos: test.rb:0

LOCALASGNNODE pos: test.rb:0

FIXNUMNODE pos: test.rb:0

NEWLINENODE pos: test.rb:1

LOCALASGNNODE pos: test.rb:1

LOCALVARNODE pos: test.rb:1

So, we can see that we have a LocalAsgnNode, representing the assignment of the following (child) FixNumNode. Then, on the next line, we can then see that we have yet-another LocalAsgnNode, but this time it has been given a LocalVarNode object as it’s assignment value. When we discuss the Dynamic Scope below, we’ll explore how these nodes actually work, but suffice it to say that when these nodes interpret, they know how to interact with their particular scope, getting and setting values, and the assignment node will ask the value node to give it the value it represents.

Context-Aware Nodes #

This is all well and good, however I glossed over how these nodes managed to show up in the tree, pre-wired to their appropriate scope. As mentioned previously, the parser consults with the StaticScope objects whenever it runs into variable assignment and references.

When the parser hits a simple ‘declaration’ (think variable reference), it makes a call into the current StaticScope object’s StaticScope.declare(ISourcePosition position,String name) method.

Similarly, when the parser hits an assignment, it tells the ParserSupport class via a call to the ParserSupport.assignable(Token,Node) method. The token represents the left-hand side of the assignment, and the passed-in node is the right-hand side of the assignment (either our FixNum or our Local variable constructed via the declaration routine we just discussed). The token is analyzed by the support class to figure out what type of variable reference it is (class variables, instance variables, globals, etc). In the case that the variable is just a standard/local identifier, the ParserSupport will ask the current static scope to help construct the node, by calling StaticScope.assign(ISourcePosition,String,Node).

This is where the two primary scope variants (block and local) diverge; the primary difference being the special scoping rules that Ruby blocks are afforded. A Ruby block is a lazy “capture” of the parent scope, yet it has its own scope as well.

Let’s walk through the local scenario first, as its the less complicated of the two. Here is what declaring a variable looks like in the local-scope scenario:

public Node declare(ISourcePosition position, String name, int depth) {

int slot = exists(name);

if (slot >= 0) {

// mark as captured if from containing scope

if (depth > 0) capture(slot);

return new LocalVarNode(position, ((depth << 16) | slot), name);

}

return new VCallNode(position, name);

}

Note that in the local case, it attempts to look up the variable by name, receiving something called a ‘slot’. If it can’t find a variable in the declaration stack, it ultimately assumes that the usage of the variable in this case must be a ‘call node’ - which in turn translates to a method call (which I have already [discussed in a previous article](«{ ref="/post/jruby/distilling-jruby-method-dispatching-101.md >}})). Ruby will then try to find that method at runtime (remember, methods, unlike local variables, can be added and removed at runtime freely).

So this is where our LocalVarNode comes from, and how it knows its position in the static scope.

public Node declare(ISourcePosition position, String name, int depth) {

int slot = exists(name);

if (slot >= 0) {

// mark as captured if from containing scope

if (depth > 0) capture(slot);

return new DVarNode(position, ((depth << 16) | slot), name);

}

return enclosingScope.declare(position, name, depth + 1);

}

The block variant is very similar, however is constructs a DVarNode instead of a LocalVarNode, and, unlike the local scenario, if it can’t find the variable in the declaration stack, it will ask the enclosing scope to figure it out, passing in an incremented-depth. This is how the block effectively tells the parent stack that it’s using a variable. As you can see, in both methods, if the depth is greater than zero, the scope internally marks that variable in that slot as “captured”; now the parent scope knows that a child scope is using one of its variables.

The ‘assign’ routines have similar parity as the ‘declare’ routines, however in that particular case, the local assign must also handle the concept of being the “top” (or root) scope of the program:

The Local Scope ‘Assign’ Routine:

public AssignableNode assign(ISourcePosition position, String name, Node value, StaticScope topScope, int depth) {

int slot = exists(name);

if (slot >= 0) {

// mark as captured if from containing scope

if (depth > 0) capture(slot);

return new LocalAsgnNode(position, name, ((depth << 16) | slot), value);

} else if (topScope == this) {

slot = addVariable(name);

return new LocalAsgnNode(position, name, slot , value);

}

// We know this is a block scope because a local scope cannot be within a local scope

// If topScope was itself it would have created a LocalAsgnNode above.

return ((BlockStaticScope) topScope).addAssign(position, name, value);

}

The Block Scope ‘Assign’ Routine:

protected AssignableNode assign(ISourcePosition position, String name, Node value, StaticScope topScope, int depth) {

int slot = exists(name);

if (slot >= 0) {

// mark as captured if from containing scope

if (depth > 0) capture(slot);

return new DAsgnNode(position, name, ((depth << 16) | slot), value);

}

return enclosingScope.assign(position, name, value, topScope, depth + 1);

}

The top scope algorithm handles the auto-declaration discussed above. If the current static scope is the top scope (such as a method, or the top of your program), then it can capture the variable for the first time (hence the ‘addVariable’ logic); if it is not, then it will ask the real top-scope (a block) to do so. From there, we can see that this is where our LocalAsgnNode comes from, and conversely, where the DAsgnNode comes from.

The handling of blocks at runtime to complement this static scoping will be discussed more below, when we get into runtime scoping rules.

Variable “Slots” #

The code above has this concept of a ‘slot’. All variables have a calculated identifier. The JRuby code describes the routine for calculating the slot variable this way:

High 16 bits is how many scopes down and low 16 bits is what index in the right scope to set the value.

In other words, variables are referenced via an integer representing a pair of values - the first portion of the number represents the scope-depth, and the second portion represents the array-index of the variable.

Both the static scope and the dynamic scope use arrays internally to hold variable information, and so when a particular piece of information for a variable is required, the correct scope is found using the high 16 bits to get the depth, and once that scope is found, the lower 16 bits are used to find the right index in the array.

This slot variable is very important as it is calculated by the parser initially, and then later will be used during the runtime to find the variable again in the scope. Obviously, serializing the local variable reference into a slot value is much cheaper than looking for the variable by name (which has to do string equality checks, rather than integer lookups in an array).

On Control Structures #

One other thing that confused me because of my Java background: control structures in Ruby (if, while, etc) do not have a distinct scope. That means this code is legal, and will print out “9”:

if some_condition

my_var = 9

end

puts "# {my_var}"

Obviously in Java, that isn’t possible; the variable goes out of scope with the “if” block.

I spent a good while analyzing the two scope implementations trying to figure out how an “if” block could fit in the picture before this occurred to me. These control blocks don’t behave like a method (where they have no parent scope), however I saw variable access and manipulation in an “if” block using LocalVarNodes and LocalAsgnNodes, which was indicating to me (erroneously) that if-blocks were using a LocalStaticScope.

The reason for this, of course, is because the “if” block just shares the scope of the parent (be it a local or a block scope), and my particular example was in a method (which is local), so I was simply being mis-lead due to my Java-ish past.

Dynamic Scoping #

DynamicScope is to the running system what StaticScope is to the parser: the DynamicScope handles the variable values, while the StaticScope tracks the variable names. In the running system, the DynamicScope and StaticScope are paired - every DynamicScope has a StaticScope peer that it consults with to figure out things about the current location. Note that the dynamic scope, unlike the static scope, is instanced out on a per-call basis. Where there will be a single StaticScope for every method, there will be a single DynamicScope for every call to a method.

Most of the runtime (including our previous LocalAsgnNode and LocalVarNode examples) use the DynamicScope object to interact with the system, and in turn, the DynamicScope makes heavy use of the StaticScope to assist with tracking variables.

As a thread is invoking a method, for example, it constructs a DynamicScope and pairs it with the static scope for that method. That scope will then be used for the lifecycle of that method execution.

Here is a description of DynamicScope from the code itself:

Represents the the dynamic portion of scoping information. The variableValues are the values of assigned local or block variables. The staticScope identifies which sort of scope this is (block or local).

Properties of Dynamic Scopes:

- static and dynamic scopes have the same number of names to values

- size of variables (and thus names) is determined during parsing. So those structures do not need to change

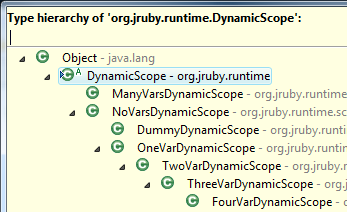

The DynamicScope class is an abstract parent to a variety of implementations (as seen in Figure 2).

(Side Note: This trend of having specialized NoArg, OneArg, TwoArg (etc.) objects shows up frequently in JRuby (usually with the word “arity” associated with it); the idea being that the ‘ManyArgs’ variant will inherently be slower and more expensive to work with, as it’s collection-based. These counted-argument implementations are bound to be a little more painful to maintain, but also provide a boost in performance for the majority of cases).

Using the Scope #

The DynamicScope class has a variety of methods on it - two of the most central to the operation of the language are #getValue(int offset, int depth), and #setValue(int offset, IRubyObject val, int depth). These two (and a ton of variants) are where the real values are actually passed to and from the activation stack of the program. As previously discussed, all variables carry an identifer that has a depth (the high-16) and an index (the low-16). The arguments to these methods (offset and depth) are those numbers.

So now, if we go back to our LocalVarNode, we can look at the interpret method of that node, and see that it does this:

@Override

public IRubyObject interpret(Ruby runtime, ThreadContext context, IRubyObject self, Block aBlock) {

IRubyObject result = context.getCurrentScope().getValue(getIndex(), getDepth());

return result == null ? runtime.getNil() : result;

}

As you can see, it simply returns the value from the current dynamic scope (as determined by the ThreadContext, which we’ll discuss shortly). You’ll see it uses ‘getIndex()’ and ‘getDepth()’ methods - here those are, using the mathematical bit-masking as discussed previously:

/**

* How many scopes should we burrow down to until we need to set the block variable value.

*

* @return 0 for current scope, 1 for one down, ...

*/

public int getDepth() {

return location >> 16;

}

/**

* Gets the index within the scope construct that actually holds the eval'd value

* of this local variable

*

* @return Returns an int offset into storage structure

*/

public int getIndex() {

return location & 0xffff;

}

Meanwhile, if we go look at the LocalAsgnNode, we’ll see it works the other way:

@Override

public IRubyObject interpret(Ruby runtime, ThreadContext context, IRubyObject self, Block aBlock) {

// ignore compiler pragmas

if (location == 0xFFFFFFFF) return runtime.getNil();

return context.getCurrentScope().setValue(

getIndex(),

getValueNode().interpret(runtime,context, self, aBlock),

getDepth()

);

}

The AsgnNode is asking the value node to interpret (which is either our FixNumNode, or in the second case, our LocalVarNode, as seen above). So in our variable-to-variable assignment, here is what is happening:

- Assignment-Node (representing ‘b’) asks Value-Node for its value.

- Value-Node (representing ‘a’) asks the current dynamic scope for its value, and returns it.

- Assignment-Node takes value and asks dynamic scope to store it for ‘b’.

That, in a nutshell, is how values are traded between scopes, and (conceptually at least) the API for using the scope is quite simple: get the current scope, and call get/set on it. Internally, the scope has all the information it needs to recursively find the correct variables to retrieve or update (whichever the case may be). “getValue” is quite straightforward at this point (this is the general purpose, ManyVars version):

public IRubyObject getValue(int offset, int depth) {

if (depth > 0) {

return parent.getValue(offset, depth - 1);

}

assertGetValue(offset, depth);

return variableValues[offset];

}

Setting is just as simple:

public IRubyObject setValue(int offset, IRubyObject value, int depth) {

if (depth > 0) {

assertParent();

return parent.setValue(offset, value, depth - 1);

} else {

assertSetValue(offset, value);

return setValueDepthZero(value, offset);

}

}

The Thread Context #

Up to this point, I have largely glossed over how the dynamic scoping gets it parentage. For static scope, we discussed that they were constructed by the parser as it scanned the program. A central component of the JRuby runtime (very central, actually) is the ThreadContext object. This is a ThreadLocal-like object (internally it uses a specialized RubyThread->SoftReference map, but the concept is roughly the same). As the runtime is executing, and is doing things like dispatching to methods, it will always consult with the ThreadContext to push and pop the dynamic scope for the current executing thread so it’s ready for the various nodes to use.

There are a number of context-specific methods on the ThreadContext - they typically start with “pre” and “post”, and are meant to be called in pairs. Let’s walk through the two most interesting scenarios, methods and blocks.

Method Dispatching and Scope #

Method invocations are always gated by calls to the correct “pre-” and “post-” methods on the ThreadContext.

ThreadContext.preMethod(...)

try {

this.call(...)

}

finally {

ThreadContext.postMethod(...)

}

In practice, it is more complicated than that, but it’s largely so that corner cases (like backtraces, and special optimizations) can be handled. Going back to the previous method-dispatching lesson, there are two methods on InterpretedMethod: “pre”, and “post” which are called as part of their ‘call’ routine (the one that interprets the AST node), and these methods in turn work with the ThreadContext pre/post methods to setup and tear-down the context as appropriate.

Here is what the method scope construction looks like on ThreadContext:

public void preMethodFrameAndScope(RubyModule clazz, String name, IRubyObject self, Block block, StaticScope staticScope) {

RubyModule implementationClass = staticScope.getModule();

pushCallFrame(clazz, name, self, block);

pushScope(DynamicScope.newDynamicScope(staticScope));

pushRubyClass(implementationClass);

}

As you can see, in this case (among some other stuff) the dynamic scope is being created to pair with the method’s static scope, and this dynamic scope has no parent (as no local variables are visible outside of the method).

Block Invocation and Variable Capturing #

One of the ‘killer features’ of modern languages is closures. If you don’t have closures, you just aren’t cool (I’m looking at you, Java). One of the oddities about closures is their ability to ‘capture’ free variables from a parent scope for their own use – of course, you have to keep in mind that the closure is going to go about its business, and may not be called for a long time after the method/parent in which it was declared has gone out of scope and left the building.

It turns out that since the parser already assigned the variables in the scope the appropriate ‘slots’, the dynamic scope, when it is being told to set a variable value or get a variable value, already knows which parent to look at; it can traverse directly to the correct depth in the parentage, and can get or set the correct index.

In other words, all of the hard work done by the parser to create the Local/Block hierarchy has effectively created an easy-to-track hierarchy for the DynamicScope. However, for that pass-through to work, the DynamicScope representing the parent method at the block’s “instantiation” point needs to be captured, and saved.

This is done by the various block implementations when they are constructed. Blocks are implemented much like methods - there is a org.jruby.runtime.BlockBody class which several real implementations extend; it’s not directly relevant enough to discuss here, but nevertheless, each implementation has a point during the constructor/initialization in which it will create a “Binding” object, which is done via a call to one of the variations of ThreadContext.currentBinding(…).

This binding object snapshots the call-frame at that point in time (along with the dynamic scope). Then, later, when the block is invoked (which an example of can be seen in InterpretedBlock.yield), it will in turn call ThreadContext.preYield*Block(…), all of which deal with the concept of invoking a block from a different context. The preYieldSpecificBlock method is relevant to this particular example. Here is what it looks like:

public Frame preYieldSpecificBlock(Binding binding, StaticScope scope, RubyModule klass) {

Frame lastFrame = preYieldNoScope(binding, klass);

// new scope for this invocation of the block, based on parent scope

pushScope(DynamicScope.newDynamicScope(scope, binding.getDynamicScope()));

return lastFrame;

}

As you can see, this is similar to the method ‘pre-’ variant, except this one does consider the binding’s dynamic scope as a parent when constructing the scope for the block invocation. This allows the previously-bound scope to be used during the invocation; any standing variables in that scope will be accessible.

Call Stack #

So far, most of the conversation has been centered around how the parser and runtime work together to ensure that the correct variables are visible and editable at the correct times. The other important task is the process of managing the call stack. This, along with creating the scope objects, is done by the ThreadContext. When a call to the thread context is made to ‘prepare’ for a method or block yield, it constructs a DynamicScope object. As the two method examples above show, however, it also puts that DynamicScope into stack-like structure on the ThreadContext (via pushScope).

This structure represents the call stack of the thread, and as method calls are made, it is manipulated via push/pop calls. In this process, JRuby seamlessly keeps the correct variables available for each method/block in the call hierarchy, and calls to ThreadContext#currentScope will always return the appropriate scope for that point in time (recall that LocalVarNode and LocalAsgnNode were given the thread context object in their ‘interpret’ call).

All Together Now #

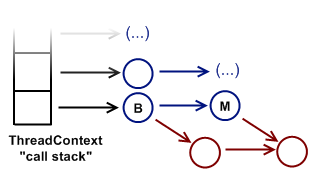

Figure 3 shows an example where current call on the stack is represented by a block’s DynamicScope (representing by the first blue node), and it’s holding a reference to another DynamicScope, which is, in this case, the scope for the method it was instantiated in (it could also alternatively be another block, and in that case this tree would recurse deeper).

The red nodes represent the corresponding static-scope objects for the block and method respectively.

Interestingly, the parent DynamicScope referenced by a block may be frozen somewhere higher up in the call stack waiting for the block to complete (such as a block passed into a ’each’ method on a collection), it could have been popped from the call stack long ago (such as when a block is used as a listener or callback on some other object), or it could even be somewhere on the call stack of another thread (which is typically seen when blocks are used as atomic units of work in a multi-threaded program).

Conclusion #

Scoping in Ruby is less rigid than many languages, so in some ways it makes this implementation less complicated, and in other ways it makes it more complicated. JRuby’s implementation of the scoping is an interesting lesson, and having gone through it, I feel like I better understand what is expected of the Ruby platform/“specification” when it comes to scoping.

Stay tuned - more to come!